Part of the “A Pioneering Cruise Line” Anthology of Stories

The Best View Of The Kimberley: From The Ocean

By Chris Done

Chris Done is Coral Expeditions’ longest-serving Guest Lecturer and has been cruising on the Kimberley coast since the company began their operations here in the second half of the 1990s. Chris’s credentials began with his formal university studies in forestry. He worked for some time in New Guinea and ended his working career in Kununurra with a long period as the Regional Manager for Conservation and Land Management of the Kimberley. Chris is also familiar with many of the other Coral Expeditions cruise itineraries where he continues to use his skills and experience as a naturalist to interpret landscapes for passengers both through his talks when onboard the Explorer or visiting a coastal site. In the following article, Chris introduces some fascinating features of the Kimberley coast.

Over the last few decades, an increasing number of Australians and foreign visitors have “done” the Kimberley. Generally, this means they have either self-driven or taken a four-wheel drive coach tour along one or both primary access roads traversing the region. Such an itinerary might be from Broome to Kununurra via the Great Northern and Victoria Highways and/or the Gibb River Road. Others may base themselves in Broome or Kununurra or, less frequently one of the other centres, and take one or several of the excellent short duration trips on offer. In all cases, the features of the Kimberley which these visitors can access provide them with memorable and graphic impressions of our very diverse region.

Land-based visitors are, however, unable to access the coast of the north and west Kimberley and it is here that are found what I believe are perhaps the best-kept secrets of Australia’s landscapes. The most spectacular features are defined by the dramatic geology of the region (as described elsewhere in this volume) and comprise cliffs, gorges, waterfalls and natural harbours. Most of these have no recognised road access and can only be reached from the coast or viewed from the air.

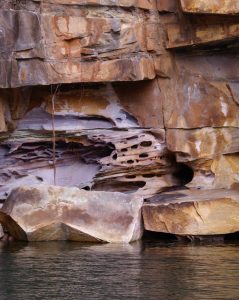

Honeycomb Erosion King George River Western Australia

From a ship-based expedition, visitors can experience close up encounters with a wide range of these features. For example, gorges such as those of King George and Berkeley Rivers are regularly accessed by small boat from the main vessel. In each case, the cliffs are impressively high and the narrow gorges which have been carved out over many millions of years by the fast-flowing rivers have much more recently (in geological terms) been flooded by the rising sea levels of the last 20,000 years that stabilised just 6,000 years ago. The zig-zagging sharp corners of the gorges have been defined by the rivers’ ability to weather and erode the weakness in the parent rock (mainly Warton Sandstone). From a distance the gorge walls appear to be relatively homogenous but close up the true colours are revealed, especially where fresh erosion allows us to see the swirls of pink and dark and light bands reflecting the dynamic forces which were at work when these sediments were laid down.

Waterfalls, seasonal in their quantity of flow, remain a highlight of these systems even during periods of low or no flow. When tides are low, the falls drop down a wide black wall, the colour of the cyanobacteria that grow during the wet season and hang on during the dry season. Honeycomb erosion can be seen high on the cliff walls adjacent to the falls, a testament to the drenching of these rocks by freshwater and salt spray during the massive flows that fill the upper reaches of these gorges during the annual summertime wet season. Further downstream from the falls, this weathering and erosion, which provides some of the most spectacular natural sculpturing imaginable, is mostly confined to within those few metres up the cliff walls that are affected by wet season floods.

Tranquil Bay, Kimberley, Western Australia.

Another frequently accessed river system is the arrow straight Prince Regent River (Gumallalla) which follows a very long line of weakness (a ‘lineament’ in this case) eroded out over millions of years by this massive river system. The further upstream you go, the higher and more precipitous are the cliffs. George Grey, who was involved in land-based exploration in the area in 1838, described “the ruins of hills” nearer the St George Basin to the lofty precipices some 40 kilometres or so inland.

Saltwater Crocodile

In each of these and other sites, it is not just about the rock. In every case, we view a great many other elements which contribute to the landscape. For example, the mangrove communities (sometimes called mangals) line the way, sometimes as a narrow band and in other areas as extensive forests. The mangroves themselves are of considerable biological interest and the intricacies of the relationships between them and their endemic and visiting fauna further emphasises the importance of the

Rainbow bee-eater. Image: David Keech

system. Crocodiles, mud crabs, fiddler crabs and mudskippers are amongst the species of fauna we see, and birders, in particular, are often rewarded with great views of

chestnut rails, great-billed herons, mangrove robins and azure kingfishers to name just a few. Less prominent is the vital role that the systems play in nurturing various fish species like barramundi, mangrove jack and fingermark bream as well as invertebrates such as prawns.

Boobook Owl, Jar Island, Western Australia

We also see areas where the stabilising effect of the mangal is quite apparent. For example, in one of the Talbot Creek inner basins, we point out a large area where fresh sediment was colonised by dense mangrove seedlings growth a decade or so ago. These seedlings are now well established and are self-thinning from what was a ‘wheat field’ type density to a more open forest of larger individual trees.

The Kimberley coast is fringed by islands with estimated numbers varying from 2000 to 3000. They range from more than 18,000 hectares to only a few. These isolated land masses are particularly crucial as ‘Island Arks’. Many of them, though, will show at least some of the features we see on the mainland and may be linked by common geology and fauna and flora, the extent of which is limited mainly by the size of an island. The presence of freshwater also determines how variable and viable flora and fauna might be, as well as human habitability. Some of the smaller islets such as Top Hat Rocks (near Low Rocks Island) and Tooth Rocks (near Bigge Island) are tiny remnants of rock (King Leopold Sandstone) which are exposed above water level and which have eroded into interesting and perhaps unexpected shapes. In each of these cases, the reference in the name is not obvious, only apparent when seen from a particular angle, while being entirely obscure from another.

Brown Boobie, Lacepede Islands, Western Australia.

Coral reef systems are perhaps not what one expects to find on the Kimberley coast. They are however a significant feature not only because of their biology but also in the way they can modify wave movements and contribute to the composition of beach sediments. They can be difficult to see due to the often turbid waters and the ever-present threat of lurking crocodiles. These factors may have contributed (along with the expense of getting there) to the relatively little research done on the Kimberley reefs until recent times.

Montgomery Reef, Buccaneer Archipelago, Western Australia

We are however fortunate to have a reef that ‘comes to us’ and which is so spectacular that many people describe it as one of the highlights of their trip to the Kimberley coast. The eminent Sir David Attenborough described it as one of the natural wonders of the world, and who would be better placed to make such an assessment. This is the fabled Montgomery Reef, where the massive reef structure appears to rise out of the ocean and shed untold billions of litres of seawater from its surface through innumerable cascades. The spectacle lasts for the whole time that the reef is exposed and during those periods we are able to explore into the heart of the system and view turtles, sea snakes and other marine life from our exploration boat and tenders. The tides too are best appreciated from the ocean, and almost everywhere we travel we see the black tide line around the rocky shores just above spring high tide level. One spectacular example of the power of the tides is at the Horizontal Falls where the impounded high tides create two tidal outrushes worthy of the title ‘waterfalls’ only to see them reverse with the incoming tide several hours later. The thrill of riding these rapids is reserved for those who visit the coast at sea level.

Humpback whale, Lacepede Islands, Western Australia

Up-close sightings of marine mammals are a bonus for many visitors to the Kimberley coast. Dugongs and dolphins reside in many parts of the region and, with luck, will be seen from time to time on many voyages. Dugongs, the plump sea cows of the Indo Pacific, have a pinkish-grey hue in the Kimberley, and mothers and calves are occasionally seen in the lower reaches of King George River. There, and in Red Cone Creek and Prince Regent River, the rare and only recently described Snub-finned Dolphin make an appearance from time to time, and Pacific Bottlenose Dolphins are likely to pay a visit at any time. A little further offshore, the annual migration of humpback whales is a feature of the later part of the dry season, and we can expect to see them from late June till perhaps late September at which time they head back on their long journey to Antarctic waters. The recovery of this population since commercial whaling ceased in the late 1960s is fantastic to see, and to know that the birthing/breeding areas are now protected by marine national park status is very comforting. Many Aboriginal art sites are only accessible from the ocean. The significance of these sites is enormous, and we are able to understand them through the increasing ability better to visit some of them under the guidance of Traditional Owners. The connection that the predecessors of the present-day guides had with the land over such a long period is extraordinary, and it is humbling to appreciate this while visiting these special places. In a short narrative such as this, it is only possible to scratch the surface of the array of features best viewed from the ocean. There are many more, and on every trip, with the exact itineraries determined by the daily tides and weather, many different aspects can be examined. This variation itself is yet another feature of interest in the Kimberley viewed from the ocean.